These are my notes from the podcast. Listen to the episode here.

From Wikipedia: Burlesque

Victorian theatrical burlesque

Victorian burlesque, sometimes known as “travesty” or “extravaganza“,[22] was popular in London theatres between the 1830s and the 1890s. It took the form of musical theatre parody in which a well-known opera, play or ballet was adapted into a broad comic play, usually a musical play, often risqué in style, mocking the theatrical and musical conventions and styles of the original work, and quoting or pastiching text or music from the original work. The comedy often stemmed from the incongruity and absurdity of the classical subjects, with realistic historical dress and settings, being juxtaposed with the modern activities portrayed by the actors. Madame Vestris produced burlesques at the Olympic Theatre beginning in 1831 with Olympic Revels by J. R. Planché.[23] Other authors of burlesques included H. J. Byron, G. R. Sims, F. C. Burnand, W. S. Gilbert and Fred Leslie.[24]

Victorian burlesque related to and in part derived from traditional English pantomime “with the addition of gags and ‘turns’.”[25] In the early burlesques, following the example of ballad opera, the words of the songs were written to popular music;[26] later burlesques mixed the music of opera, operetta, music hall and revue, and some of the more ambitious shows had original music composed for them. This English style of burlesque was successfully introduced to New York in the 1840s.[27]

Sheet music from Faust up to Date

Some of the most frequent subjects for burlesque were the plays of Shakespeare and grand opera.[28][29] The dialogue was generally written in rhyming couplets, liberally peppered with bad puns.[25] A typical example from a burlesque of Macbeth: Macbeth and Banquo enter under an umbrella, and the witches greet them with “Hail! hail! hail!” Macbeth asks Banquo, “What mean these salutations, noble thane?” and is told, “These showers of ‘Hail’ anticipate your ‘reign'”.[29] A staple of burlesque was the display of attractive women in travesty roles, dressed in tights to show off their legs, but the plays themselves were seldom more than modestly risqué.[25]

Burlesque became the speciality of certain London theatres, including the Gaiety and Royal Strand Theatre from the 1860s to the early 1890s. Until the 1870s, burlesques were often one-act pieces running less than an hour and using pastiches and parodies of popular songs, opera arias and other music that the audience would readily recognize. The house stars included Nellie Farren, John D’Auban, Edward Terry and Fred Leslie.[24][30] From about 1880, Victorian burlesques grew longer, until they were a whole evening’s entertainment rather than part of a double- or triple-bill.[24] In the early 1890s, these burlesques went out of fashion in London, and the focus of the Gaiety and other burlesque theatres changed to the new more wholesome but less literary genre of Edwardian musical comedy.[31]

From Wikipedia: Dundreary

Lord Dundreary is a character of the 1858 British play Our American Cousin by Tom Taylor. He is the personification of a good-natured, brainless aristocrat. The role was created on stage by Edward Askew Sothern.[1] The most famous scene involved Dundreary reading a letter from his even sillier brother. Sothern expanded the scene considerably in performance. A number of spin-off works were also created, including a play about the brother.[citation needed]

His name gave rise to two eponyms rarely heard today: Dundrearies were a particular style of facial hair taking the form of exaggeratedly bushy sideburns, also called dundreary whiskers. They were popular between 1840 and 1870 and in England were called Piccadilly weepers.[2]

“Dundrearyisms” were expanded malapropisms in the form of twisted and nonsensical aphorisms in the style of Lord Dundreary (e.g., “birds of a feather gather no moss”). These enjoyed a brief vogue.[citation needed]

Charles Kingsley wrote an essay entitled, “Speech of Lord Dundreary in Section D, on Friday Last, On the Great Hippocampus Question”, a parody of debates about human and ape anatomical features (and their implications for evolutionary theory) in the form of a nonsensical speech supposed to have been written by Dundreary.[3]

From Traditional Tune Archive: Cruiskeen Lawn

CRUISKEEN LAWN (Cruiscin Lan). AKA – “Crooskeen Lawn,” “Crúisgín Lán (An).” AKA and see “O’Sullivan’s Return,” “Men of ’82 (The),” “Wife Who Was Dumb (The),” “Dumb Dumb Dumb.” Irish, Air (4/4 time). G Minor (O’Neill): A Minor (O’Farrell, O’Flannagan): C Minor (Haverty). Standard tuning (fiddle). AB (O’Flannagan, O’Neill): AABB (O’Farrell). “Cruiskeen Lawn” is the Englished form of the Gaelic title Cruiscin Lan/Crúisgín Lán (An) which means ‘The Full Little Jug’.

YouTube: The Clancy Brothers performing “Cruiskeen Lawn”

(Fire and the connection to Lee’s surrender are follow-ups from episode 33)

(use the second one, from April 11th)

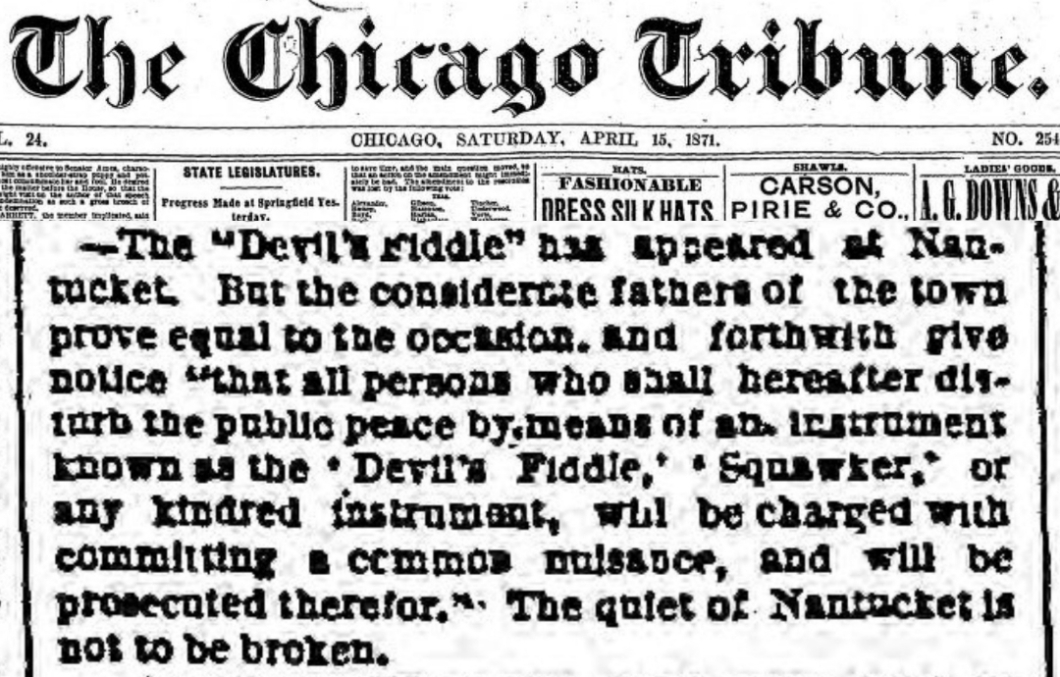

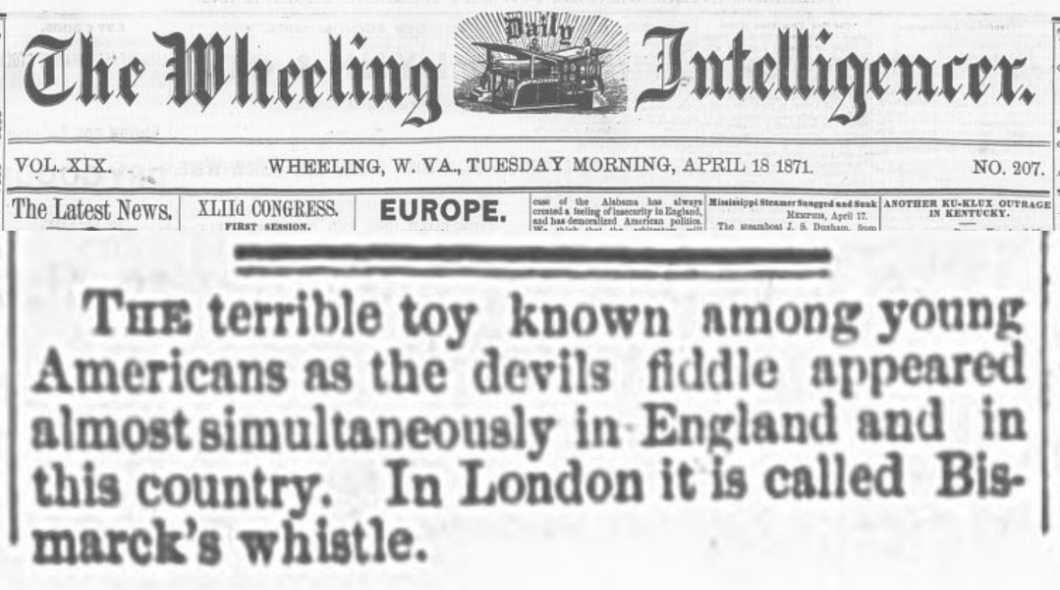

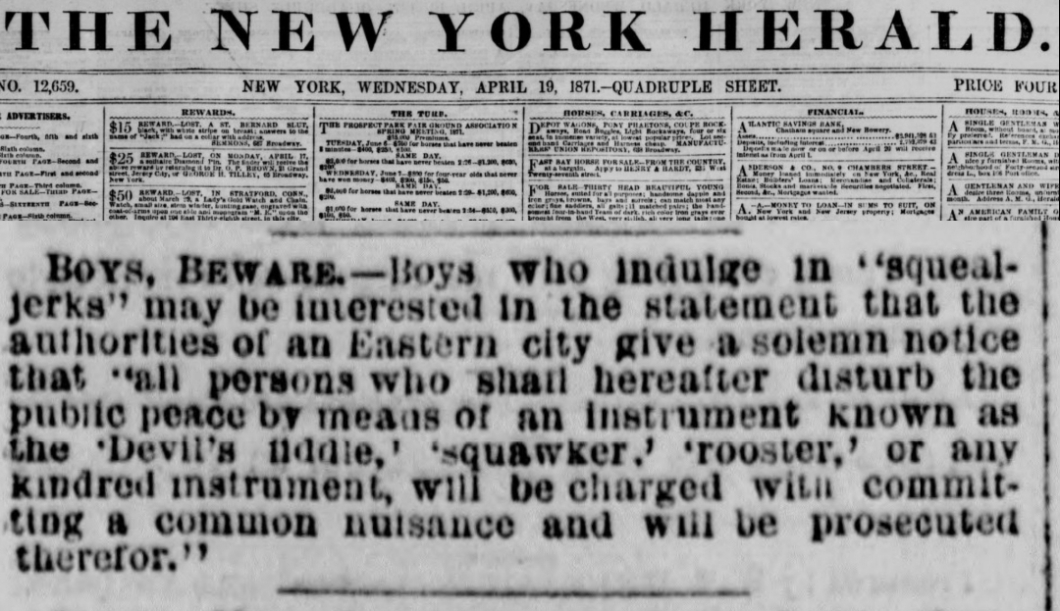

First instance I can find of of Nantucket piece, but it refers only to “an eastern city”.

Weymouth, MA (couldn’t find front page)

(Read from the second one, from April 10th)

Read the Weekly Caucasian’s full coverage of the State Editorial Convention on Chronicling America.

From The Magician’s Own Book, 1871: